Students have a great deal to contribute to school improvement.

We made this point in a previous blog post What the school improvement Gurus are not yet talking about.

Many schools are currently promoting ‘student voice’ – a feature of many school improvement models. However our experience shows that this rarely extends beyond a Student Representative Council where a few selected students have the responsibility to collect periodic feedback from students or engage with school fundraising activities. This is a limited view of student voice.

Quality Learning theory emphasises the importance of working together to improve and involving the ‘worker at the front line’ in improving the system. In schools this is the student.

Student contribution begins in the classroom

Students’ potential to lead improvement begins in the classroom. Every student can reflect upon what helps him or her to learn and what hinders learning. Students, with their teacher, can use Quality Learning tools to share, explore and prioritise these driving and restraining forces. A Parking Lot is a good way to collect this data on an ongoing basis. (See our previous blog post Put up a Parking Lot!)

John Hattie in his book Visible Learning (2009) discusses feedback as in the ‘top 10’ greatest influences on student learning. He emphasises the importance of of student-to-teacher feedback (not just the more commonplace teacher-to-student kind).

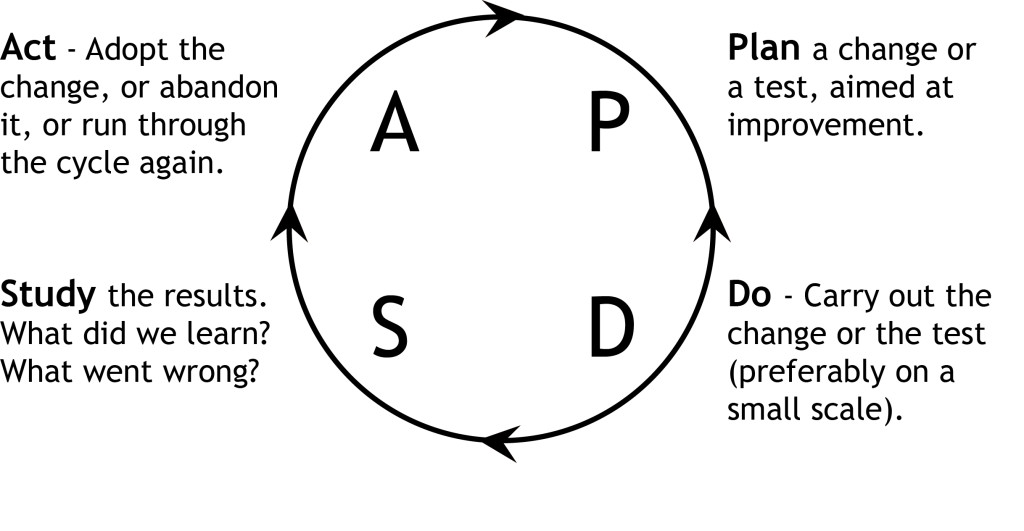

Based on considered student feedback, teachers and students can jointly design and trial changes to classroom processes, with the aim of improving learning. The class can evaluate the effectiveness of these changes over time. The changes can then be:

- adopted as ongoing practice;

- adapted, modified and trialed again;

- or abandoned.

In this way, students engage in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle of learning and improvement.

Engaging students in classroom improvement like this has four key benefits.

- Teachers can learn a great deal from listening to their students discuss what helps and hinders their learning. This also develops student metacognition and builds capacity in ‘learning how to learn’.

- Engaging students in the PDSA cycle of improvement teaches them a practical ‘how to’ approach to improvement, which they can then apply to their own opportunities for improvement. These lessons have practical application beyond schooling.

- Engaging students in improving their own situation builds student ownership of the process and outcomes. The teacher has the active support of students in developing, trialling and evaluating a jointly developed theory for improvement.

- If the trial is successful, student learning will improve. If it is not successful, students have benefited from experience with the PDSA cycle. An alternative theory can be developed and trialled.

Student contribution to whole-school improvement

In addition to contributing to improving learning in the classroom, students have a significant contribution to make to whole-school improvement. In most schools, this potential remains unexplored, let alone realised.

There are many more students than adults (teachers, administrators and support staff) in most schools. While student-teacher ratios vary enormously by school type and sector, it is generally true that students outnumber adults by more than five to one in most schools. In some places, the ratio is more than ten to one.

The adult populations in schools are diverse; this is even more so for most student populations. There is a rich diversity of backgrounds, languages, cultures, experiences and skills in both the adult and student populations in all schools. This is more pronounced in some schools than others, but it is always present. (Such is the nature of variation in social systems).

Yet in most schools, school improvement is the domain of adults alone.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

The enormous potential of student creativity remains untapped in most schools. Young people have not yet learned some of the constrained thinking that we tend to acquire through life. Students can ask the obvious questions that we don’t even see and have ideas for improvement we could never dream of.

Hallett Cove R-12 School

Student Improvement Teams

Students can lead and participate in improvement teams to address key issues of concern. We have worked with student teams over many years on school, community and industry-based improvement projects. They have never failed to do a remarkable job.

Students from the Student Leadership Team at Hallett Cove R-12 School in South Australia recently participated in a rigorous process of school improvement using the PDSA cycle.

Ten teams were formed looking at issues that affected them within their school.

The objectives of the process were for students to:

- learn more about the Quality Learning approach to improvement

- learn first-hand about managing and improving organisations

- develop skills in teamwork, goal setting, time management and communication

- reflect upon and share what was learned

- make significant improvements to the school and classroom!

The process comprised three phases:

- Training Day

- Four-day PDSA School Improvement Experience

- An Evaluation Meeting.

The Training Day introduced the knowledge and skills needed to participate in the improvement process. This training included the Principles of Quality Learning and some of the Quality Learning tools.

Phase 2 was where the bulk of the work was done. Students analysed a school situation or process, using the PDSA cycle and Quality Learning tools, to understand the system, identify root causes, develop solutions and make recommendations. To do this the used the following process (and tools):

1 Select the team

1.1 How will team members work together? (Code of Cooperation)

1.2 How will the team keep track of ideas and issues? (Parking Lot)

2 Clarify the opportunity for improvement

2.1 Precisely what is the opportunity for improvement? (Problem Statement)

2.2 Who are the clients and what do they need? (Perception Analysis)

3 Study the current situation

3.1 What is the current process flow, policy and/or state of relationships? (Deployment Flow Chart and/or Affinity Diagram)

4 Analyse the causes

4.1 What are the possible causes of variation and poor performance? (Fishbone Diagram)

4.2 What are the root causes of variation and poor performance? (Hot Dot and Interrelationship Digraph)

4.3 What data are needed to measure performance? (Measures Selection Matrix)

4.4 What do the data say about current performance? (Check Sheets, Run Charts, Pareto Charts)

5 Develop a theory for improvement

5.1 What are the possible solutions, and which will have the greatest impact? (Potential Improvements Matrix)

5.2 What are the recommendations for action, including time lines and responsibilities? (Gantt Chart)

5.3 How will the recommendations be communicated?

On the final afternoon, teams presented their findings to the school leadership team. The other Student Teams were also present. Their findings were presented as a written report and a presentation.

The Evaluation Meeting occurred in the days following the report presentation and provided an opportunity to give feedback to the school about their experience.

The many excellent recommendations were acted upon in the weeks that followed, and have made lasting and significant improvements to the school.

In the words of Andrew Gohl, Assistant Principal:

The PDSA cycle provides a structure and a clear process that people can work through, that is inclusive of all voices: regardless of whether you are the very young, the very old, the very vociferous, the very quiet. There’s a clear process there for everyone to have a voice, for everyone to be heard. And, of course, in that inclusiveness, the outcome is one which meets everybody’s needs.

Watch the video that tells the story of the Hallett Cove R-12 School Student Teams.