In this post, we consider how the concepts of accountability, responsibility and authority are being applied in the name of school improvement. We explain why a strong focus on tightening accountability is unlikely to result in improvement in schools (or any other organisations for that matter).

We defined accountability:

Accountability: the collection of outcomes that an individual is charged to produce and for which the individual can be held to account

Note that we defined and discussed accountability, responsibility and authority in detail in the previous post.

An accountability approach to school improvement

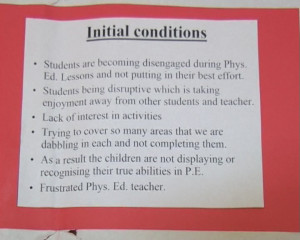

The drive to hold educators to account for improving performance has become stronger in recent years. Considerable effort has been expended clarifying the accountabilities and responsibilities of school leaders across many jurisdictions.

Sadly, tightening accountabilities is unlikely to lead to improved performance.

Here’s why.

Intent

There is one benefit to be derived from clarifying accountabilities and responsibilities. Doing so makes clear what is agreed to be important and how performance will be measured. This focuses attention, which can be beneficial. This is particularly beneficial when the process of agreeing and accepting accountabilities is open and collaborative. For example, team members can agree to take on specific tasks between meetings; each agrees to be accountable to the team for their actions. This can be affirming and effective.

Where organisations take a more formal approach to assigning accountability, it becomes problematic.

Assumptions

The accountability approach to school improvement is based on many questionable assumptions.

Held to account?

What does it mean to be held to account? It can be a requirement to explain what happened, or didn’t happen. It can also mean criticism, blame and punishment. Whatever the meaning, being judged is implicit in the definition.

Routinely passing judgements upon one another is not a feature of highly trusting or collaborative relationships and can be toxic.

Sufficiently comprehensive?

Establishing the specific outcomes for which one will be held to account does focus attention, but this can be at the expense of other areas requiring attention. The approach assumes that all the important outcomes have been identified and codified into accountabilities. This is rarely achieved. The current attempts to hold educators to account for student performance based on standardised testing, for example, is leading some to focus attention on the content to be tested; this can be at the expense of other areas of learning.

It is very difficult to establish an accountability system to address all stakeholders needs.

Numerical goals and targets.

Frequently, accountabilities are expressed as numerical goals or targets, which, it is assumed, can be measured accurately. We discussed in chapter five of our book Improving Learning that numerical goals and targets can lead to distortions of the data and/or the system. Each year the newspapers report cases of teachers and schools ‘cheating’ on high-stakes tests. Unachievable numerical goals may be at the heart of the clean diesel scandal at VW.

As Dr. Deming said, “Fear invites wrong figures.”

Locus of control.

It is assumed that an individual has sufficient control over the activities and results for which they are accountable to ensure the outcomes are met. This is not always the case. A teacher, for example, can have almost no control over the home life of his or her students, which has a very significant impact on the student’s learning.

It hardly seems reasonable to be held accountable for things outside one’s control.

Stable and capable processes?

The processes in which the individuals work are assumed to be stable and capable. In other words, it is assumed that the processes are predictable and producing desirable results, making achievement of the accountabilities possible. As we highlighted in chapter two of Improving Learning:

Many processes in school education are not capable.

Motivation?

The approach is based in the assumption that individuals require extrinsic motivation. Motivation has been discussed at length in an earlier series of posts.

Extrinsic motivation factors focus attention on obtaining the rewards and avoiding the punishments; not on the intrinsic value of the tasks themselves.

Negotiated?

While there is, in theory, scope for negotiation of accountabilities, in practice many are established historically and imposed – top-down. It is the people doing the daily work of the system that best know what needs improving. In particular, they know the barriers to improvement, which can frequently only be addressed by individuals more senior to them.

Top-down imposition of accountabilities may address management’s priorities, but are likely to neglect root causes of waste, frustration and poor performance.

Interdependence.

Each individual, being held to account for specific outcomes, is based on an assumption of independent relationships within the organisation: each party acts with autonomy towards their own goals.

Relationships in organisations are far more interdependent than autonomous.

Optimisation of the whole.

A system of accountabilities across an organisation may seek to optimise the performance of the organisation as a whole; there is an assumption that optimising each part of the system will optimise the whole. As we discussed in chapter three of Improving Learning the opposite is true.

By optimising the parts, the whole will be sub-optimised.

On balance, it would appear that focussing on systems to tighten accountabilities holds little promise for delivering improvement. Not only is it difficult to develop and sustain accountability systems within organisations, doing so is based on questionable assumptions. Furthermore, to date, it has demonstrated little systemic improvement.

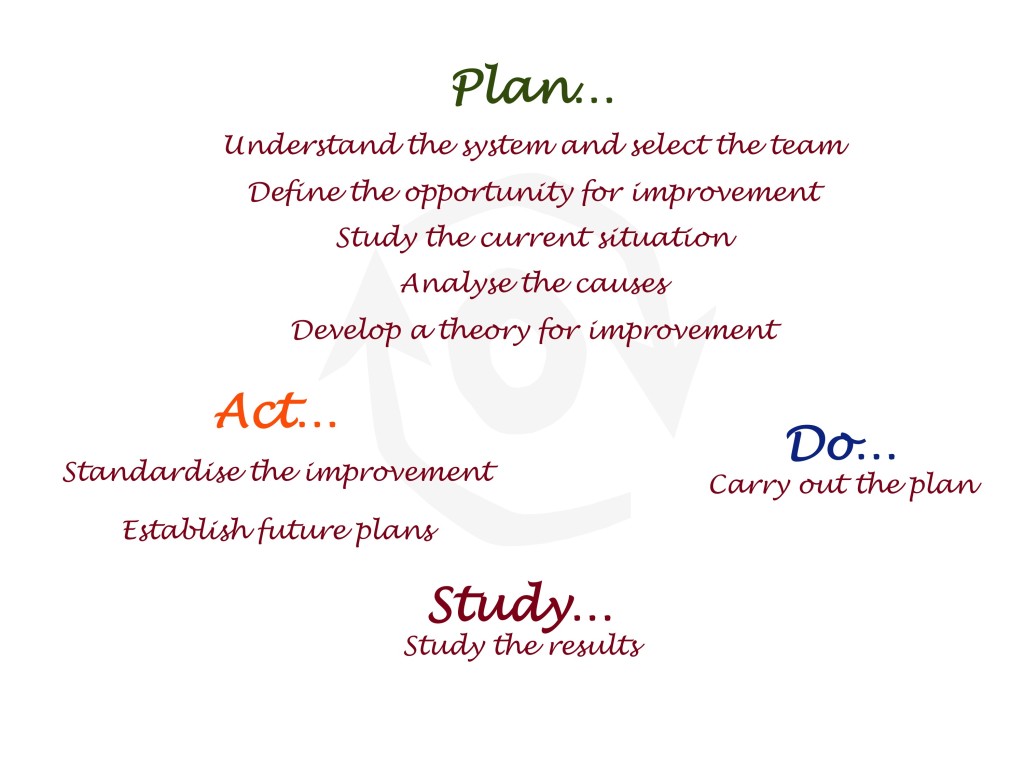

An alternative

If accountability is not a viable route to improved performance, what should be done instead?

The answer is as simple as it is complex:

Equip everybody so they can work with others to improve the systems of learning for which they are responsible.

The theory and practices are described in detail in our book Improving Learning: A how-to guide for school improvement.