Creating a theory for improvement

Continual improvement is derived, in large measure, from the efforts of individuals and teams working together to bring about improvement. For example, many schools have introduced professional learning teams (PLTs). PLTs usually involve teams of teachers working together on agreed improvement projects aimed at improving classroom learning and teaching practice.

Sadly, ‘how’ we work on these improvement efforts is frequently left to chance. The result is valuable time and effort wasted as sub-optimal solutions are derived. So how can we make the most of these rich opportunities to improve?

The answer lies in applying a scientific approach to our improvement efforts – a structured learning and improvement process. Many know this as action learning or action research. We call it PDSA: the Plan-Do-Study-Act improvement cycle.

The history of PDSA

The PDSA cycle is attributed to the work of Walter Shewhart, a statistician working with the Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York during the 1930s (although it can be traced back further to John Dewey’s profound writings on education in the 1800’s).

Shewhart was the first to conceptualise the three steps of manufacturing — specification, production, and inspection – as a circle, rather than a straight line. He observed that when seeking to control or improve quality, there must be reflection upon the outcomes achieved (inspection) and adjustments made to the specifications and production process.

He proposed the move from this:

To this:

You may notice similarities with the traditional teaching methods of plan, teach, and assess.

In recent times there has been a focus in schools on “assessment for learning” (in contrast to “assessment of learning”). It parallels Shewhart’s observation of the need to close the loop in manufacturing.

Shewhart went on to identify the three steps of manufacturing as corresponding to the three steps of the dynamic scientific process of acquiring knowledge: making a hypothesis (or theory), carrying out an experiment, and testing the hypothesis (see Figure 4).

Source: Adapted from Walter Shewhart, 1986, Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control, Dover, New York, p. 45.

With these thoughts, Shewhart planted the seeds for W. Edwards Deming to develop the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, which was published as the Shewhart cycle in 1982. Deming taught the Shewhart cycle to the Japanese from 1950 who picked it up and renamed it the Deming Cycle.

The PDSA Cycle

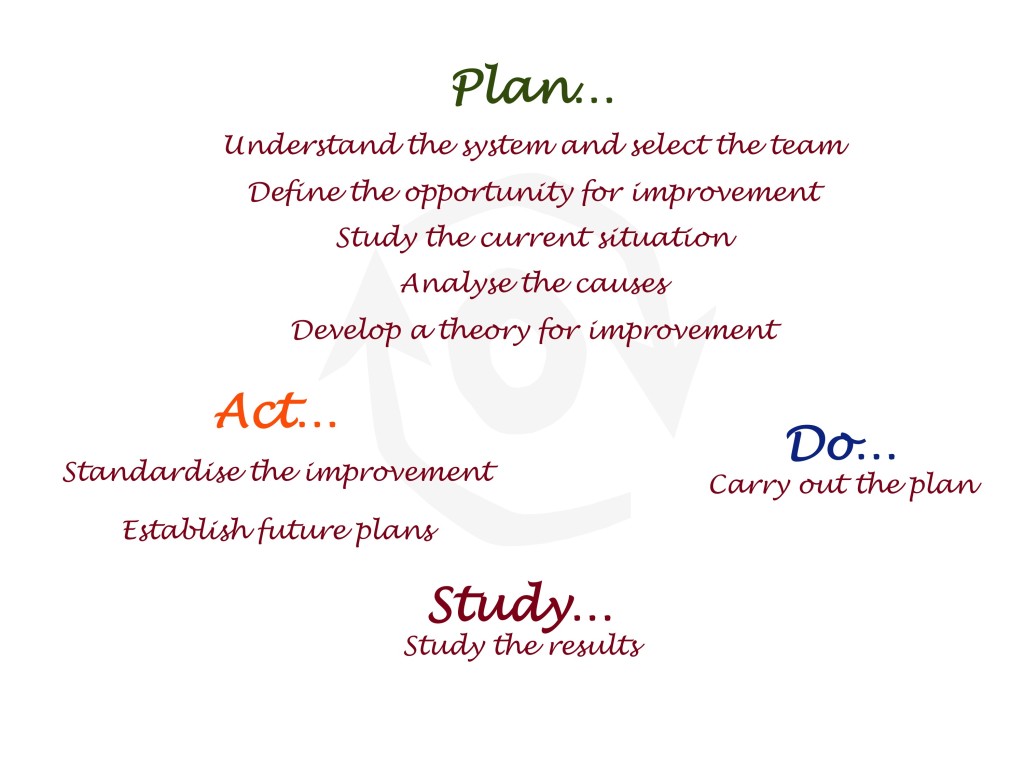

Deming published the cycle in The New Economics in 1993, as the Plan–Do–Study–Act (PDSA) cycle. He changed “check” to “study” in order to more accurately describe the action taken during this step. PDSA is the name by which the cycle has become widely known in recent times. (Figure 5.)

Source: W. Edwards Deming, 1993, The New Economics: For industry, government, education, MIT, Cambridge.

The Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle is a structured process for improvement based on a cycle of theory, prediction, observation, and reflection.

There are, of course, many variants of the improvement process, with many and varied names. In overview, the concepts are the same.

There is a strong tendency for people to want to race through the “plan” stage and get straight into the “do” stage. Schools in particular find it difficult to make time for the reflective step of “study”. Many individuals and teams just want to get into the action and be seen to be making changes, rather than reflecting on whether the change has been an improvement, or just a change.

A detailed and structured process

Where an improvement opportunity is of a significantly complex nature, a comprehensive application of the PDSA process is necessary.

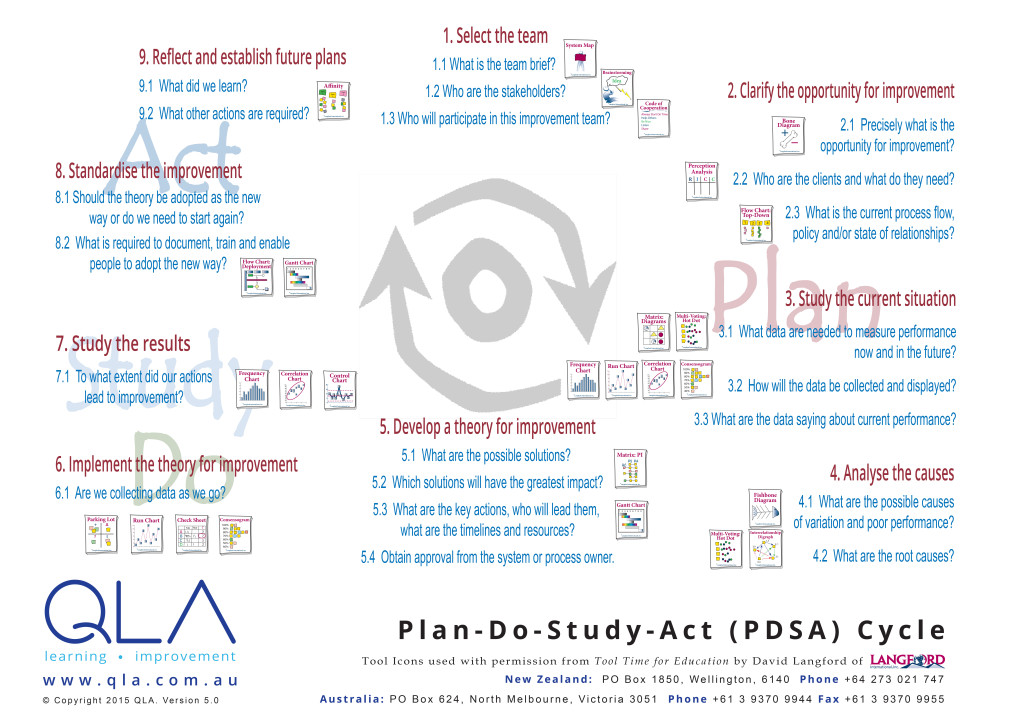

Our work in industry, government and education over the past two decades has shown the nine step PDSA process, illustrated in Figure 6, to be particularly effective. This nine step process has been compared with dozens of alternate models of PDSA and refined over the past two decades.

In developing such a process, there is a balance to be struck between the technical considerations of having a robust process that will deal with diverse contexts and issues, and the simplicity that makes the improvement process accessible and practical for busy people. Over the years, we have continually sought to simplify the model to make it more accessible. For nearly a decade, the nine steps have remained constant, but the specific actions and tools comprising each step have been progressively refined.

The process has beed designed to ensure it meets the criteria necessary to achieve sustainable improvement, namely:

- Be clear about mutually agreed purpose

- Establish a shared vision of excellence

- Focus upon improving systems, processes and methods (rather than blaming individuals or just doing things)

- Identify the root causes of dissatisfaction, not the symptoms

- Carefully consider the systemic factors driving and restraining improvement, including interaction effects within the system and with containing systems

- Identify strengths to build upon as well as deficiencies to be addressed

- Identify the clients of the improvement efforts and understand their needs and expectations

- Achieve a balance in addressing the competing, and sometimes contradictory, needs and expectations of stakeholders in improvement efforts

- Be clear about the theory for improvement, and use this to predict outcomes

- Reflect on the outcomes of improvement efforts, in the context of the selected theory for improvement, in order to refine the theory for improvement

- Use operational definitions to ensure clarity of understanding and measurement

- Not copy others’ practices without adequate reflection about their proper implementation in a new context — adapt not adopt.

These requirements have been reflected in the nine step PDSA improvement process shown in Figure 6.

To provide clear guidance, we have developed a comprehensive PDSA chart (Figure 7). The PDSA improvement process is framed as a series of questions to be answered by the improvement team (or individual). These questions address the considerations necessary to achieve sustainable improvement as detailed above. The process also refers the user to specific quality learning tools that can be used to address the questions, promoting collaboration and evidence-based decision-making.

This is not a perfect process for improvement — there is no such thing. It is a process for improvement that can be adapted (not adopted), applied, studied, and improved. It can be used as a starting point for others, like you, who may wish to create a process of their own.

There are enormous benefits to applying a standard improvement process: an agreed improvement process that everybody follows. This can be standard across the school or whole district. Everyone can use the same approach, from students to superintendent. The benefits, apart from maximising the return on effort, time and resources, include having a common and widely used model, language, set of concepts, and agreed tools. It also establishes an agreed process that can itself be reviewed and improved, with the contribution of everybody in the organisation.

Watch a video of PDSA applied to year one writing.

Watch a video of PDSA applied within a multi-age primary classroom.

Read or watch a video about student teams applying PDSA to school improvement.

Download the detailed nine-step PDSA chart.

Purchase IMPROVING LEARNING: A how-to guide for school improvement to read more about the quality improvement philosophy and methods.

Purchase our Learning and Improvement Guide: PDSA Improvement Cycle.

One thought on “Plan-Do-Study-Act”