What is your school’s theory of teaching and learning?

Some schools waste time focusing their efforts on trying to control and manage the actions and behaviours of individuals. They would do better examining the underpinning theory, systems and processes driving the action and behaviour. Reflecting deeply on, and defining (making explicit), the beliefs upon which current approaches to learning and teaching are based, can lead to great focus, alignment and return on efforts to improve.

Fundamental to improving learning is to agree (define) the theory guiding our teaching and learning.

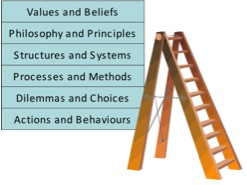

The following anthropological model adapted from the work of Martin Weisbord can help us understand why this is so. It describes a hierarchy of influences on organisational behaviour. The model is consistent with Deming’s teachings on how systems drive performance and behaviour, and the need to develop theory to drive improvement.

Weisbord’s model illustrates the relationship between beliefs, philosophy (theory), systems, processes, choices and action. An organisation’s systems and processes reflect and reinforce its values, beliefs and philosophy. These systems and structures dictate the processes and methods, and shape the dilemmas and choices faced by individuals of the organisation. The choices made by individuals, in turn, produce the actions and behaviours we observe.

Let’s look at an example to illustrate. Say we believe students are inherently lazy, that they have little desire to improve, and need to be motivated to learn. We will then develop systems and processes in our school and classrooms in an attempt to extrinsically motivate them. Our systems and processes will usually be based upon incentives and rewards, fear and punishment. If, however we believe we are born with an innate desire to learn and to better ourselves, and that the motivation to learn comes from within, then we will design very different systems of learning in our classrooms. These systems usually focus upon building ownership of learning, and working with students to identify and remove the barriers to their intrinsic motivation and learning.

Defining a theory and designing systems and processes can be a deliberate and thoughtful action or it can occur through natural evolution – the choice is ours.

We can make a conscious choice to define and make explicit our values and beliefs regarding teaching and learning. An operational definition is used to achieve and document a shared understanding of the precise meaning of concept/s. Operational definitions provide clarity to groups of individuals for the purposes of discussion and action.

It follows that once we have defined our theory of teaching and learning, we can design structures, systems, processes and methods that are aligned to it and naturally promote the actions and behaviours we desire.

Of course, we draw upon evidence-based research to craft our theory. We can then work together over time testing, reinforming and reaffirming this theory, and improving systems and processes to produce the performance and behavioural outcomes we wish to see.

How to…

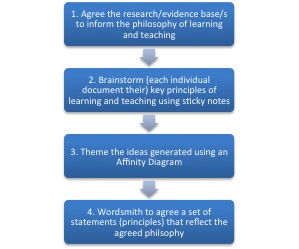

Our work with schools in defining a learning and teaching philosophy has typically followed the process summarised in the flowchart below. All staff are invited to be involved in agreeing the philosophy which takes place through one or more workshops.

Step 1. Agree a research or evidence-base to inform the philosophy

The first step is to agree and draw upon a research or evidence-base to inform the philosophy. Education systems in Australia have, over time, adopted different pedagogical models. Schools have adopted many different models, all purporting to reflect the latest research and providing the theory necessary to guide excellent teaching practice. The Quality Teaching model, the National School Improvement Tool, the e5 Instructional Model, and the International Baccalaureate are examples of pedagogical models currently in use. Explore the preferred model/s with all staff before defining your philosophy to agree which one or more resonate and align with the needs of your learning community. Of course, if there is a model that adequately describes the philosophy to teaching and learning that your school community wishes to adopt, the job is made easier. Job done – just agree to use it!

Step 2. Brainstorm ideas

Something we tend to overlook is to recognise the ‘prior knowledge’ of our teachers. Every educator will have developed a theory – based upon their understanding and experience – as to the greatest influences on learning in their classroom. Ask staff also to reflect upon their own teaching and learning values and beliefs. We have found it helpful to express the learning and teaching philosophy as a set of (documented) principles.

To define the philosophy, ask staff to brainstorm their key learning and teaching beliefs, concepts and principles. This can be achieved by every staff member providing their input to the process by writing down their individual ideas as statements on sticky notes – one statement per sticky note.

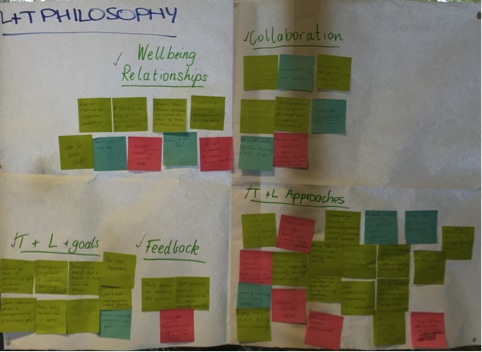

Step 3. Collate the ideas using an Affinity Diagram

The staff input can then be collated by creating an Affinity Diagram with the sticky notes. Headings are applied to the Affinity Diagram reflecting the agreed major themes (as in the figure below).

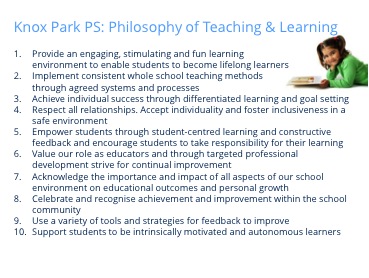

Step 4. Agree theory statements

These themes can be documented as a set of agreed statements (principles). For example, the following are the principles of learning and teaching agreed to by Knox Primary School in Melbourne, Victoria.

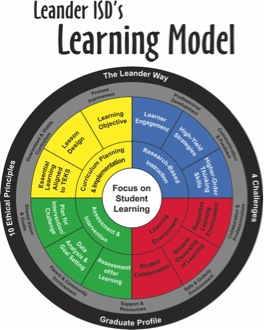

Here is another example of an agreed learning and teaching philosophy. It is the Learning Model developed by the Leander Independent Schools District in Texas, USA.

The theory as a foundation for continual improvement

The school’s theory of learning and teaching, or principles, are then used as an ongoing reference to develop, review and continually improve consistency in policy and practice across the school. Each principle is subject to ongoing exploration through reflection and dialogue to develop deeper and shared understanding, and to inform the development of agreed learning systems and processes – the school’s pedagogical framework.

Naturally, the philosophy is dynamic. Like any theory or hypothesis, to be relevant and effective in an ongoing way, it will need to be regularly reviewed, reaffirmed or reinformed by further research and our experiences of applying it over time.

A final note

John Hattie’s research (Teachers Make a Difference: What is the research evidence? Australian Council for Educational Research, October 2003) revealed greater variation between the classrooms in an Australian school than between Australian schools. Defining the theory that will guide teaching and learning across your school is a way to reduce this variation.

To learn more…

Purchase a copy of Improving Learning: a how to guide to school improvement.