We have worked with many schools over the last 15 years, each one committed and working really hard to continually improve. Yet our experience shows few have established an effective process to capture the many improvements they make. Organisational improvement is quickly lost where there is not a process in place to hold the gains made.

So what is your approach to capture organisational learning?

Ours is system documentation.

System documentation

System documentation is the term we use to describe a structured and disciplined approach to capture organisational knowledge, learning and improvement. It relates to a collection of key documents that reflect the way in which an organisation conducts its business.

Excellent system documentation:

- provides a central repository of documents critical to the running of the organisation that are readily accessed and understood by everyone

- has an easy-to-use format and structure that facilitates documentation, stakeholder involvement, and the capturing of organisation innovation and improvement

- is regularly reviewed for effectiveness and efficiency

- is easily maintained, updated and distributed

- has one person assigned to oversee its ongoing review, consistency and improvement.

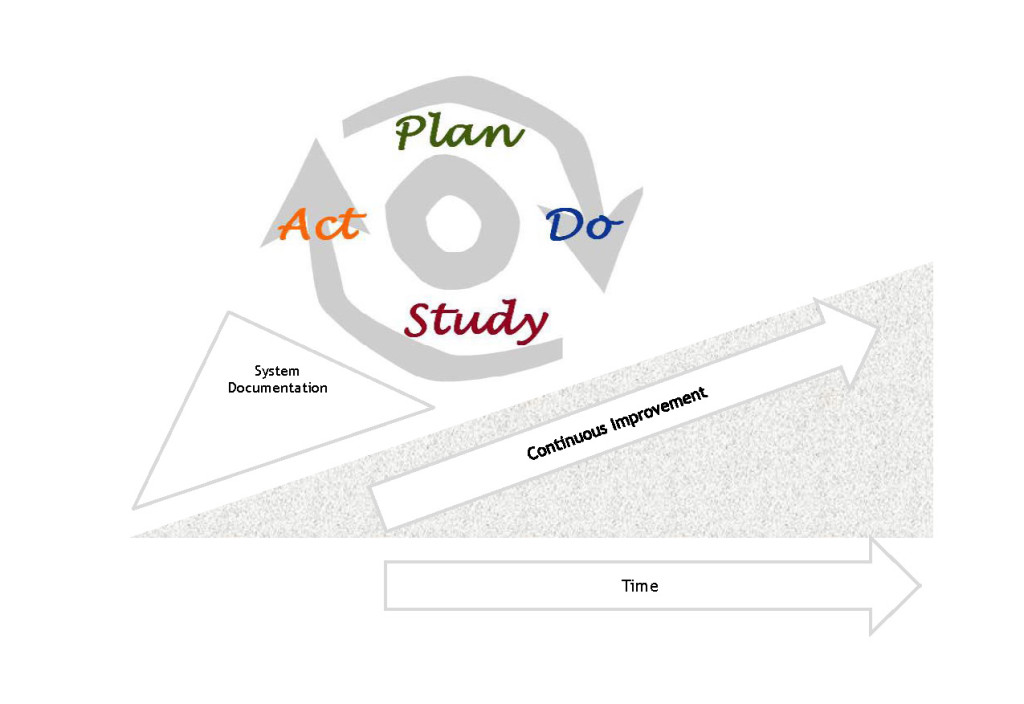

System documentation: ‘the chuck under the continuous improvement wheel’

How to…

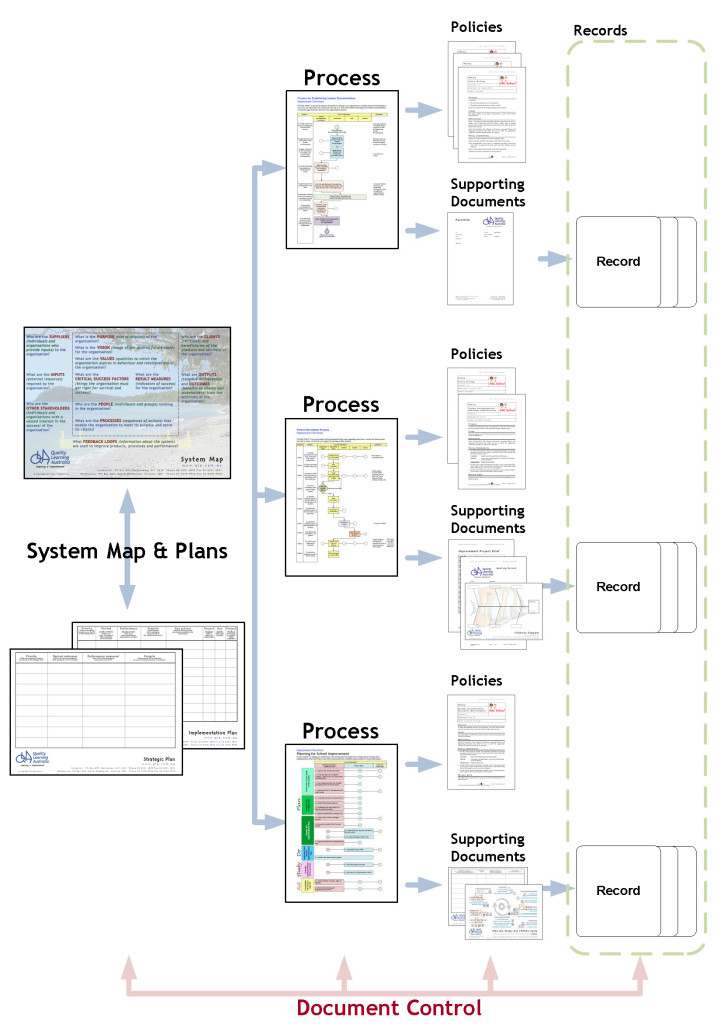

We have found the following structure for system documentation to be effective and efficient.

Suggested components of system documentation

Usually in electronic form, the documentation comprises:

- school directional and planning documents

- processes (procedures) describing methods, sequencing and responsibilities

- policies describing what the organisation will do with respect to a particular endeavour and why (policies relate to processes and supporting documents)

- supporting documents – standard documents pertaining to a specific process or policy, including: templates, letters, forms, presentations, etc.

- records – documents containing data, facts, information and/or evidence relating to the organisation’s operations

- document control which facilitates the identification and locating of documents and ensures people have the latest version of the right document.

We believe there are several key steps to getting started with system documentation:

- Assign one person to oversee the design, implementation and improvement of the system documentation process.

- Agree a structure and index and establish folders.

- Place all existing processes, policies and supporting documents into the folders (they will quickly accumulate and can reviewed later on).

- Agree a format for processes, policies and supporting documents

- Agree and document a document control policy and associated processes (how will documents be uniquely identified?).

- Begin by documenting a new process, related policy and supporting document that will immediately add value or reduce risk. Involve key stakeholders to build ownership and understanding.

- Encourage people to document processes, policies and supporting documents as they engage with them to build the system over time.

The benefits

There are many benefits to having effective system documentation. These include:

- Increased accessibility to important documents. (Often in schools, these documents are scattered across different people’s computers, or worse still; are to be found only in the heads of those who left the school last year!)

- Openness, transparency and accountability

- Effective communication

- The basis for inducting, training and mentoring staff and other stakeholders

- Consistency of approach (agreement as to ‘our best known way’)

- Providing the foundation necessary for ongoing reflection, review, continual improvement and innovation.

Learn more…

View a video clip on system documentation.

Purchase a System Documentation Guide

Register to receive updates on other Quality Learning resources

Register to receive updates on the forthcoming Quality Learning book – Improving Learning: learning a guide to school improvement