This is the final in a series of four blog posts to introduce the underpinning concepts related to variation in systems. In the first post we discussed common cause and special cause variation. The second explored the concept of system stability. The third explained system capability. This final post discusses tampering – making changes to systems without understanding variation. Tampering makes things worse! This is an edited extract from our book, Improving Learning.

Stop tampering

Let us begin with a definition of tampering.

Tampering: making changes to a system in the absence of an understanding of the nature and impact of variation affecting the system

The most common forms of tampering are:

- overreacting to evidence of special cause variation

- overreacting to individual data points that are subject only to common cause variation (usually because these data are deemed to be unacceptable)

- chopping the tails of the distribution (working on the individuals at the extreme ends of the distribution without addressing the system itself)

- failing to address root causes.

Tampering with a system will not lead to improvement.

Let us look more closely at each of these forms of tampering and their impact.

Tampering by overreacting to special cause variation

Consider the true story of the young teacher who observed a student in the class struggling under the high expectations of her parents. The teacher thought that the student’s parents were placing too much pressure on the child to achieve high grades, which the teacher believed to be beyond the student. The young and inexperienced teacher wrote a letter to the parents suggesting they lower their expectations and lessen the pressure on their daughter. Receipt of this letter did not please the parents, who demanded to see the school Principal. Following this event, the Principal required all correspondence from teachers to parents to come via her office. Faculty heads within the school, not wanting to have teachers in their faculties make the same mistake, required that correspondence come through them before going to the Principal.

The end result was a more cumbersome communication process for everyone, which required more work from more people and introduced additional delays. The principal overreacted to a special cause. A more appropriate response would have been for the principal to work one-on-one with the young teacher to help them learn from the situation.

Making changes to a system in response to an isolated event is nearly always tampering.

A more mundane example of this type of tampering is when a single person reports that they are cold and the thermostat in the room is changed to increase the temperature. This action usually results in others becoming hot and another adjustment being made. If any individual in the room can make changes to the thermostat setting, the temperature will fluctuate wildly, variation will be increased and more people will become uncomfortable, either too hot or too cold.

Most people can think of other examples where systems or processes have been changed inappropriately in response to isolated cases.

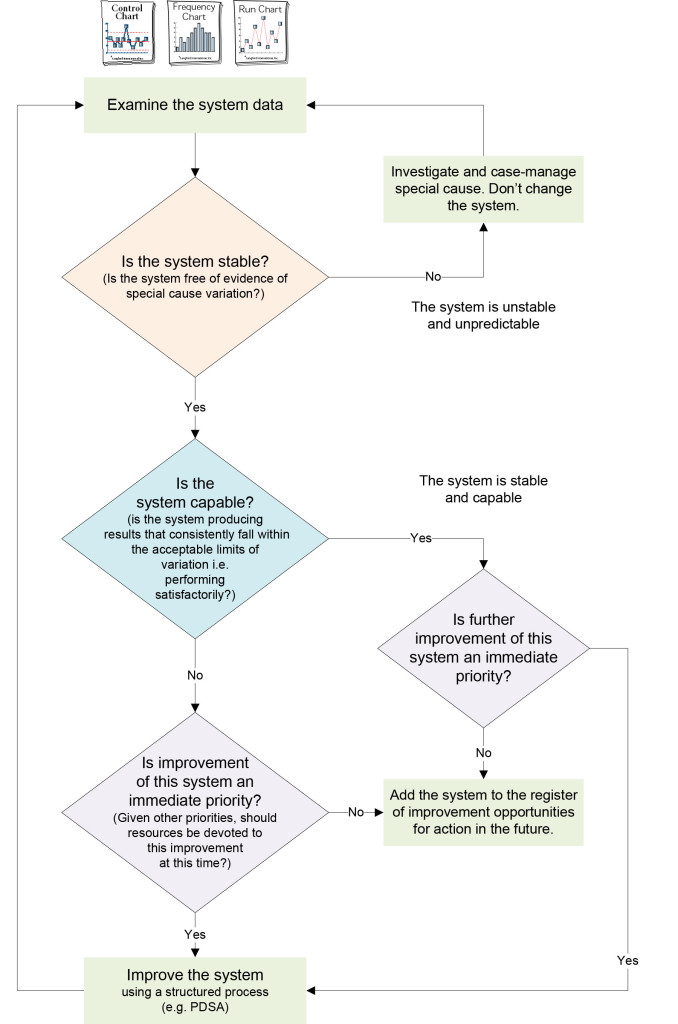

The appropriate response to evidence of special cause variation is to seek to understand the specific causes at play and have situations dealt with on a case-by-case basis, without necessarily changing the system.

Occasionally, investigation of a special cause may reveal a breakthrough. The breakthrough may be so significant that changes to the system are called for in order to capitalise on the possibilities. This is, however, rare and easily identified when it is the case.

Tampering by overreacting to individual data points

Another common form of tampering comes from overreacting to individual data points. Such tampering is very common and very costly.

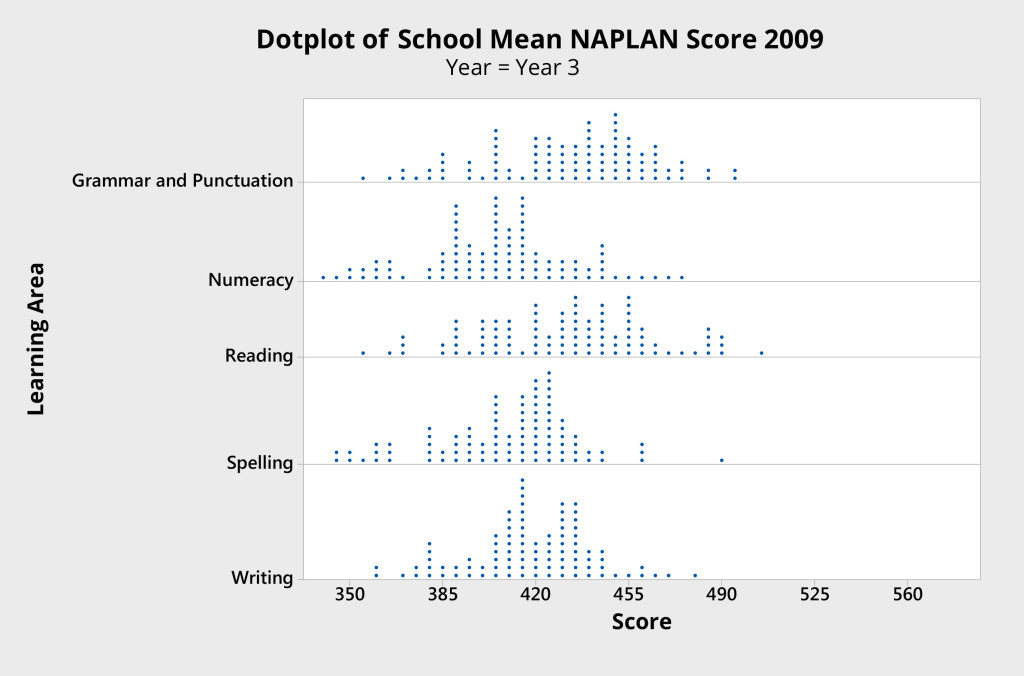

Figure 1 presents a dot plot of mean Year 3 school results, measured across five key learning areas by NAPLAN in 2009. These results are from an Australian jurisdiction and include government-run schools and nongovernment schools. For the purpose of the argument that follows, these data are representative of results from any set of schools, at any level, anywhere.

The first thing to notice is that there is variation in the school mean scores. (Normal probability plots suggest the data appear to be normally distributed, as one would expect.) The system is stable and is not subject to special causes (outliers).

The policy response to variation such as this is frequently a form of tampering. Underperforming schools are identified at the lower ends of the distribution and are subjected to expectations of improvement, with punishments and rewards attached.

This response fails to take into account the fact that data points within the natural limits of variation are only subject to common cause variation.

To single out individual schools (classes, students, principals or teachers) fails to address the common causes and fails to improve the system in any way.

When this approach is extended to all low performing elements, it becomes an even more systematic problem: attempting to chop the tail of the distribution.

Tampering by chopping the tails of the distribution

Working on the individuals performing most poorly in a system is sometimes known as trying to chop the tail of the distribution. This is also tampering.

There are three main reasons why this is bad policy, all of which have to do with not understanding the nature and impact of variation within the system.

Firstly, it is not uncommon to base interventions on mean scores. Yet it is well known within the education community that there is much greater variation within schools than there is between schools. Similarly, there is much greater variation within classes than between classes within the same school. Averages mask variation.

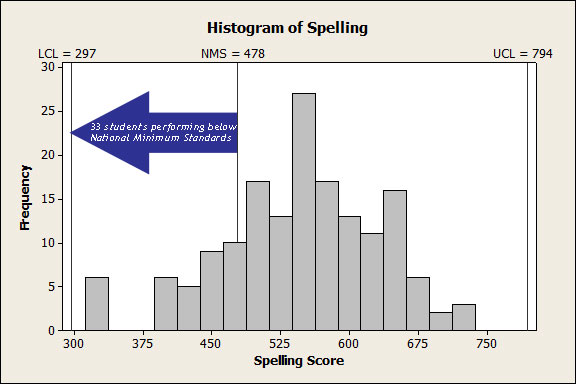

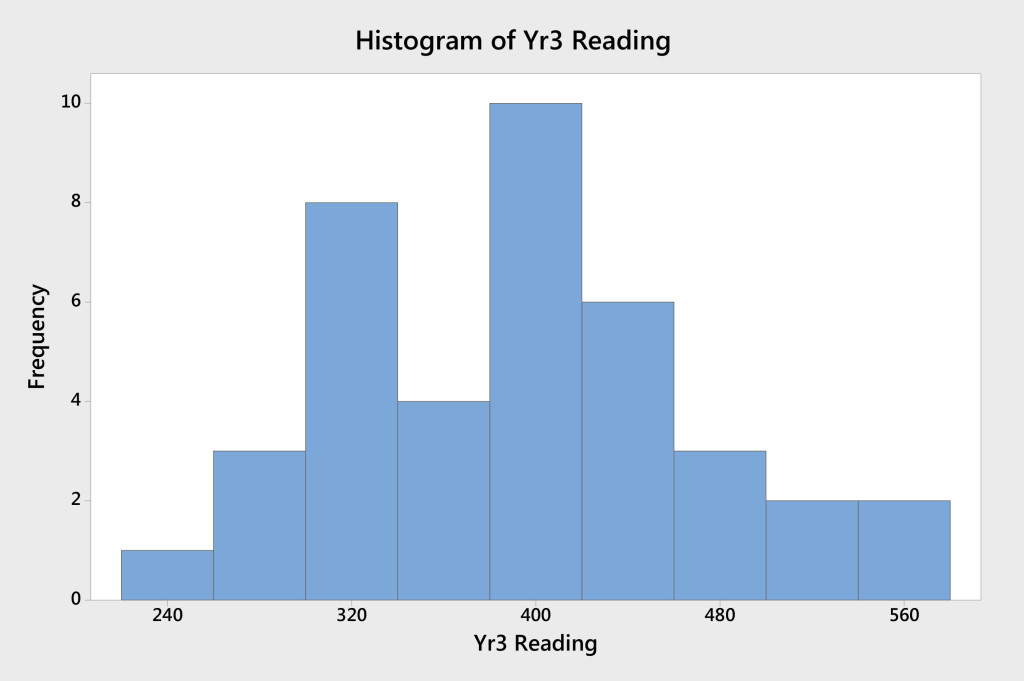

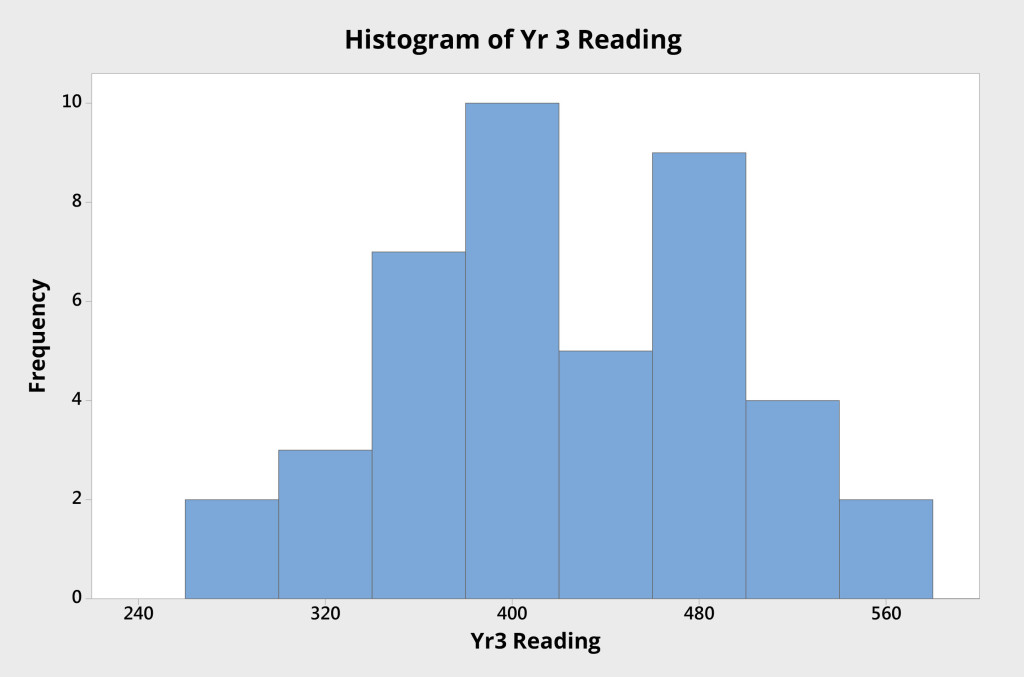

Consider two schools. School A (Figure 2) is performing at the lower end of the distribution for reading scores — with a mean reading score of approximately 390. School B (Figure 3) has a mean reading score approximately 30 points higher.

The proportion of students in each school that is performing below any defined acceptable level is fairly similar. School A, for example, has 12 students with results below 350. School B has seven. In some systems, resources are allocated based on mean scores. Those with mean scores beyond a defined threshold are entitled to resources not available to those with mean scores within certain limits. If School A and School B were in such a system and the resourcing threshold was set at 400, for example, School B could be denied resources made available to School A, simply because its mean score is above some defined cut-off point.

Where schools or classes are identified to be in need of intervention based on mean scores, the nature and impact of the variation behind these mean scores is masked and ignored. If the 12 students in School A receive support, why is it denied to those equally deserving seven students in School B?

Secondly, the distribution of these results fails to show evidence of special cause variation. The variation that is observed among the performance of these schools is caused by a myriad of common causes that affect all schools in the system.

Singling out underperforming schools for special treatment each year does nothing to address the causes common to every school in the system, and fails to improve the system as a whole.

Even if the intervention is successful for the selected schools, the common causal system will ensure that, in time, the distribution is restored, with schools once again occupying similar places at the lower end of the curve. The system will not be improved by this approach.

Thirdly, this approach consumes scarce resources that could be used to examine the cause and effect relationships operating within the system as a whole and taking action to improve performance of the system as a whole.

In education, working on the individuals performing most poorly in a system is a disturbingly common approach to improvement. It never works. A near identical strategy is used within classes to identify students who require remediation. The “bottom” — underachieving — kids are given a special program; they are singled out. Sometimes the “top” — gifted and talented — kids are also singled out for an extension program.

This is not so say that we should not intervene when a school is strugglingor when a student is falling behind. Nor are we suggesting that students and schools who are progressing well should not be challenged to achieve even more. It is appropriate to provide this support and extension to those who need it. The problem is that doing so does not improve the system. Such actions, when they become as entrenched as they currently are, are merely part of the current system.

It should be noted that focussing upon poor performers also shifts the blame away from those responsible for the system as a whole and onto the poor performers.

The mantra becomes one of “if only we could fix these schools/students/families”. The responsibility lies not with the poor performers, but with those responsible for managing the system: senior leaders and administrators. It is a convenient, but costly diversion to shift the blame in this way.

If targeting the tails of the distribution is the primary strategy for improvement, it is tampering and it will fail. Unless action is taken to improve the system as a whole, the data will be the same again next year, only the names will have changed. Over time, targeting the tails of the distribution also increases the variation in the system.

This sort of tampering is not restricted to schools and school systems. It is very common, and equally ineffective, in corporate and government organisations. It is quite common that the top performers are rewarded with large bonuses, while poor performers are identified and fired or transferred. Sales teams compete against each other for reward and to avoid humiliation. Such approaches do not improve the system; they tamper with it.

Tampering by failing to address root causes

Tampering commonly occurs when systems or processes are changed in response to a common cause of variation that is not a root cause or dominant driver of performance.

People tamper with a system when they make changes to it in response to symptoms rather than causes.

It is easy to miss root causes by failing to ask those who really know. Who can identify the biggest barriers to learning in a classroom? The students.

Teachers can be quick to identify student work ethic as a problem in high schools. It is a rare teacher who identifies boring and meaningless lessons as a possible cause. Work ethic is a symptom, not a cause. It is not productive to tackle the issue of work ethic directly. One must find the causes of good and poor work ethics and address these in order to bring about a change in behaviour.

There has been a concerted effort in recent years in Australia to decrease class sizes, particularly in primary schools. Teachers are pleased because it appears to reduce their work load and provides more time to attend to each student. Students like it because they may receive more teacher attention. Parents are pleased because they expect their child to receive more individualised attention. Unions are happy because it means more teachers and therefore more members. Politicians back it because parents, teachers and unions love it. Unfortunately, the evidence indicates that these changes in class size have very little impact on student learning. (See John Hattie, 2009, Visible Learning, Routledge, London and New York.) This policy is an example of tampering on a grand and expensive scale. Class size is not a root cause of performance in student learning.

Managers need to study the cause and effect relationships within their system and be confident that they are addressing the true root causes. Symptoms are not causes.

Every time changes are made to a system in an absence of understanding the cause and effect relationships affecting that system, it is tampering.

Tampering will not improve the system; it has the opposite effect.

Read about four types of measures, and why you need them.

Read about common cause and special cause variation.

Read about system stability.

Read about system capability.

Read more in our comprehensive resource: IMPROVING LEARNING – A how-to guide for school improvement.

Purchase our learning and improvement guide Using data to improve.